In 1931, researchers working in the south of France discovered a large mussel at the entrance to a cave. Inconspicuous at first glance, it languished in the collections of a nearby natural history museum for decades.

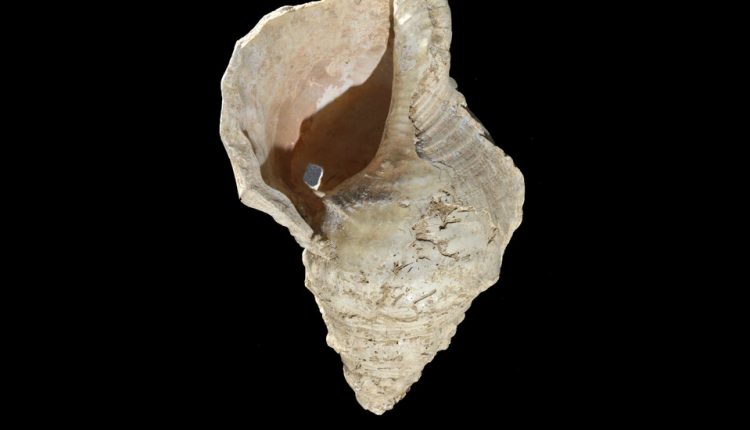

Now a team has re-analyzed the mussel shell, which is around one meter long, using modern imaging technology. They concluded that the shell had been deliberately struck and pierced to turn it into a musical instrument. It is an extremely rare example of a “conch shell” from the Paleolithic, the team concluded. And it still works – a musician recently pulled three notes out of the 17,000-year-old shell.

“It took a lot of air to keep the sound going,” said Jean-Michel Court, who conducted the demonstration and is also a musicologist at the University of Toulouse.

The Marsoulas Cave at the foot of the French Pyrenees has long fascinated researchers with its colorful paintings depicting bisons, horses and people. It was here that the huge, light brown conch shell was first discovered, an unsuitable object that must have been transported from the Atlantic Ocean more than 150 miles away.

Despite its weight, the shell of the sea snail Charonia lampas was gradually forgotten. Presumably nothing more than a drinking vessel, the mussel sat in the Natural History Museum of Toulouse for over 80 years.

It wasn’t until 2016 that the researchers began to analyze the shell again. Artifacts like this seashell help paint a picture of how cave dwellers lived, said Carole Fritz, an archaeologist at the University of Toulouse who has studied the cave and its paintings for over 20 years. “It’s difficult to study cave art without a cultural context.”

Dr. Fritz and her colleagues first assembled a three-dimensional digital model of the mussel. They noticed immediately that some parts of the bowl looked strange. For starters, part of his outer lip had been knocked off. That left a smooth edge, in complete contrast to Charonia Lampas, said Gilles Tosello, a prehistoric and visual artist also at the University of Toulouse. “Usually they are very irregular.”

The tip of the clam was also broken off, the team found. This is the toughest part of the shell, and it is unlikely that such a break would have occurred naturally. Indeed, further analysis revealed that the shell had been hit repeatedly – and accurately – near its tip. The researchers also noticed a brown residue, possibly remnants of clay or beeswax, around the broken tip.

The mystery deepened when the team used CT scans and a tiny medical camera to examine the inside of the clam. They found a hole about half an inch in diameter that ran inward from the broken point and pierced the inner structure of the shell.

All of these modifications were by design, the researchers believe. The smoothed outer lip would have made it easier to hold the clam, and the broken tip and adjacent hole would have made it possible to insert a mouthpiece – possibly the hollow bone of a bird – into the shell. The result was a musical instrument, the team concluded in their study published in Science Advances on Wednesday.

This shell could have been played during ceremonies or used to call gatherings, said Julien Tardieu, another Toulouse researcher who studies sound perception. Cave settings tend to amplify the sound, said Dr. Tardieu. “Playing that clam in a cave could be very loud and impressive.”

It would have been a nice sight too, the researchers suggest, because the shell is decorated with red dots that have now faded to match the markings on the walls of the cave.

That discovery is believable, said Miriam Kolar, an archaeoacoustician at Amherst College in Massachusetts who studies conch shells but was not involved in the research. “There is compelling evidence that the bowl was modified by humans into a sound-producing instrument.”

While other “conch horns” have been found in New Zealand and Peru, none is as old as this conch.

Dr. Fritz said it was incredible Dr. Court to hear the shell play. His music had not been heard by human ears in many millennia, which made the experience particularly moving, she said.

“It was a fantastic moment.”

Comments are closed.